I’m writing you this letter from home, where more often than not, I’m just sitting quietly, and doing nothing. Tokyo isn’t on a strict lockdown but the government has asked us to stay home and other than trips to the grocery store and walks along the riverside, I’m doing my best to comply.

I imagine many of you are in a similar situation. This new idleness brings up a lot of emotions, frustration, fear, sadness, loneliness. Over the past month, I’ve been digging into the Zen Buddhist tradition and I am hoping to offer some words of comfort:

“As muddy water is best cleared by leaving it alone, it could be argued that those who sit quietly and do nothing are making the best possible contributions to a world in turmoil.”

In this quote Alan Watts is referring to the act of meditation when he says “sit quietly and do nothing” but in our current situation, I also think sitting on your couch, and absentmindedly scrolling through old photos applies. Here are a few other Zen teachings that I’ve particularly appreciated at this moment that I’d like to share with you.

Focusing on the Details

The 'focus on the details' especially relates to the theme of many Zen poems. The poems aren’t about grand philosophies of life but about the easily overlooked elements like sounds in the forest or the moon shining through the clouds. These poetic reminders help me notice the joys in my slightly-shrunken-social-distancing universe.

Making his way through the crowd

In his hand

A poppy.

— Issa (1763 - 1827)

Distant mountains

Reflected in the eyes

Of a dragonfly.

—Issa (1763 - 1827)

To those who only pray for the cherries to bloom

How I wish to show the spring

That gleams from a patch of green

In the midst of the snow-covered mountain village.

—Fujiwara Iyetaka (12th century)

Tending Toward Wabi (Non-attachment)

My previous understanding of 'Wabi' was in connection with the idea of perfectly imperfect. But after reading DT Suzuki's "Zen and Japanese Culture", I now associate 'Wabi' with non-attachment, letting go of desires. When you are okay not having every desire fulfilled, then, whatever happens, is perfect, even if imperfect. This kind of thinking gives me great ease as 2020 is shaping up VERY differently than I had previously imagined!

“Wabi means insufficiency of things, inability to fulfill every desire one may cherish, generally a life of poverty and dejection.”

Another story I love in relation to 'Wabi' is about the Silver Temple in Kyoto, also known as Ginkakuji. Both the Golden (Kinkakuji) and Silver (Ginkakuji) Temples were originally retirement villas for Shoguns (military rulers of Japan) and then transitioned to Zen Temples. The Golden Temple was built by Shogun Ashikaga Yoshimitsu in 1397. This was considered to be the epitome of temples, covered in the most highly prized metal, gold. Years later, in 1490, when Ashikaga Yoshimitsu’s grandson, Ashikaga Yoshimasa, went to build his retirement villa he decided to build the temple in an inferior metal, silver. Due to war, the construction of the villa was never completed and the silver foil never applied to the exterior. But actually, in its incomplete state, the temple is even more beautiful than it’s sister temple in the West of the City. The Silver Temple, Ginkakuji, is by far one of my favorite temples in Kyoto.

Kinkakuji, Golden Temple, Kyoto

Ginkakuji, Silver Temple, Kyoto

Spending Time in Nature

It’s interesting, but the major Zen Temples in both China and Japan were referred to as mountains (Five Mountains of Kyoto). There is such a strong connotation of Zen practitioners taking themselves away to the mountain monastery to meditate, that even when temples were found in the center of Kyoto or Kamakura, it was still referred to as ‘a mountain.’ At the beginning of this month I was able to travel down to Kyoto and visit on the Zen Monastery’s there, Daitokuji, it was explained to me, that the gates that separated the temple grounds from the general walking areas were meant to act as a portal and transport the visitor from the city to the mountains where they could do their spiritual work. Living in the city, I don’t have easy access to mountains, but instead, I’ve been using my daily walks along the riverside to connect. And as with Zen, where the change of seasons is highlighted and prized, I’ve been cherishing the change each day in the blossoms on the cherry trees.

“Changeability is frequently the object of admiration.”

Here's a video my husband, Eiji, helped me put together to show the change in the blossoms each day.

Ritualizing the Everyday

DT Suzuki said, “The Japanese are great in changing philosophy into art, abstract reasoning into life.” One of the clearest examples of this translation of Zen philosophy into art is the tea ceremony. Practicing Zen is to practice "seeing reality directly" and when you practice the art of tea, the actions before, during, and after are meant to cleanse the sense doors (sight, smell, sound, taste, touch) of the practitioner, so they come away with a cleansed spirit.

“When water is poured into the bowl, it is not water alone that is poured into it—a variety of things go into it, good and bad, pure and impure, things about which one has to blush, things which can never be poured out anywhere except into one’s own deep unconscious.”

While I don’t have a tea practice, I treat the preparation of my morning coffee as a mini “tea ceremony,” focusing on doing just what I’m doing and not multitasking. Sharing the cup of coffee with my partner with full heart and sincerity and taking the time to drink it in and enjoy the moment. If I can carry the quality of present moment awareness with me into the rest of my day, it’s a gift to be treasured. Especially during these unprecedented times when the news takes over all my attention, every moment of the day is an opportunity to practice zen whether it be cooking, cleaning, or even lying down.

Embracing Absurdity and Spontaneity

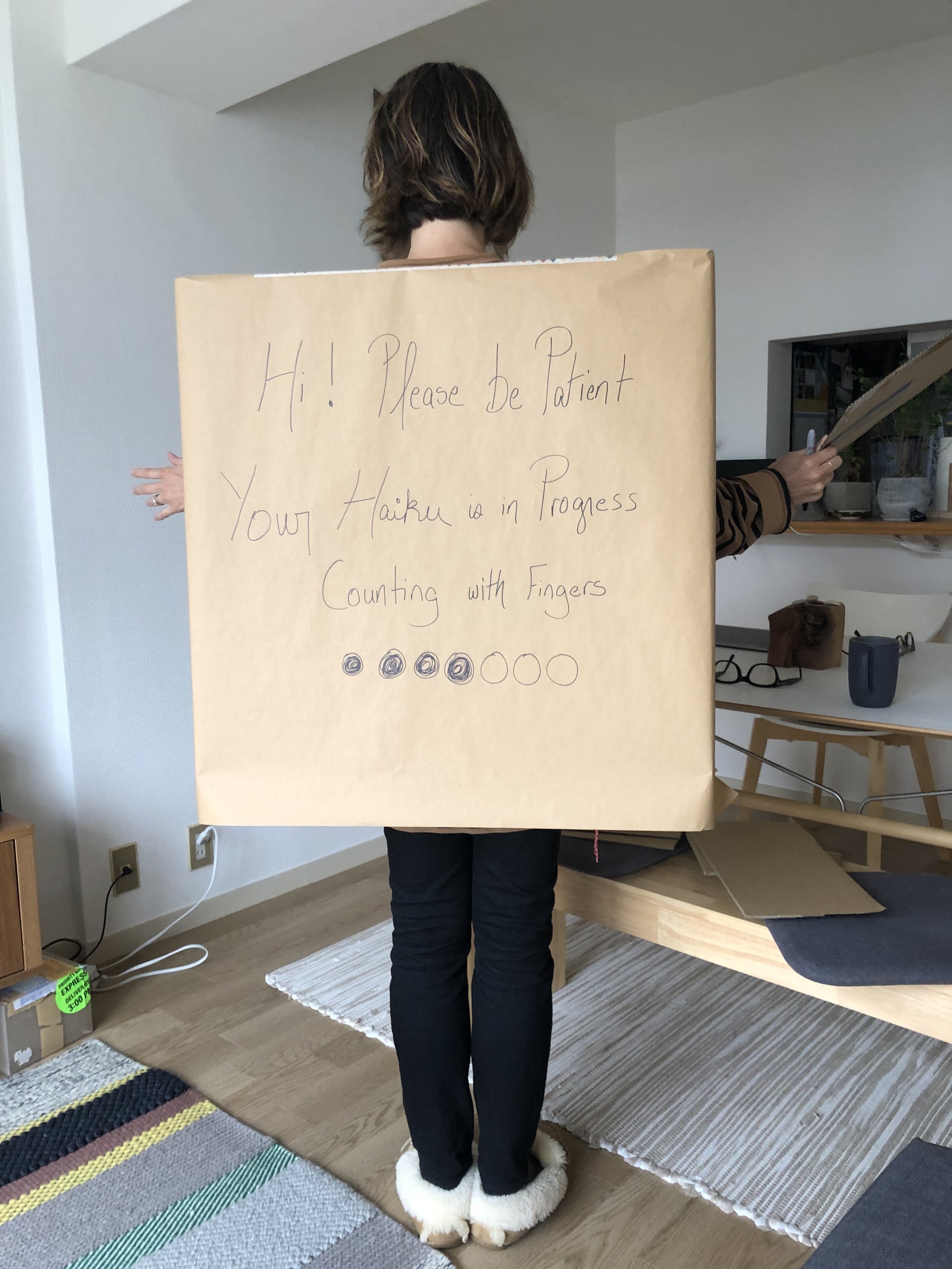

I’m not sure how many of you are on Instagram but earlier this month my family put on a talent show. I decided that my talent was to be a robot that could produce haikus based on topics from the audience, it was absurd, yes! and it was an answer that just came to me, without much thought. Was it ‘talent’? Not really. But that’s not what matters because it was a very spontaneous response that was true to who I am.

Spontaneity in the Zen Buddhism tradition relates to the practice of koans (mind puzzles) that help students of zen realize the ultimate teachings. Often teachers engage in a question and answer session with their students and a perfectly appropriate answer to the question “What is this jar, if not used for carrying water?” is to kick the jar over. It’s a spontaneous, non-conceptual response that maintains the “reality” of the moment. It perplexes me how it answers the question, but that doesn’t matter, I’m still too much of a novice to attempt such koans.

Non-striving

Zen claims that all humans have Buddha-nature, an awakened presence filled with compassion and wisdom, and since humans are inherently good, to do actions in the hopes of accumulating merit is pointless. Furthermore, the motivation behind the action takes away from its sincerity.

“All beings by nature are Buddhas,

as ice by nature is water.

Apart from water there is no ice;

apart from beings, no Buddhas”

I've been conflicted that I'm not doing enough, but I have to go back to the idea that sitting quietly and doing nothing, is in itself something quite impactful. In "Zen and Japanese Culture" Suzuki mourns that “we moderns have lost the taste for leisureliness, that we find no room in our worrying hearts for enjoying life in any other way than running after excitement for excitement’s sake.” With our new-found time at home and some of these Zen perspectives, I think we may be able to prove Mr. Suzuki wrong!

I loved all the Haiku topics I received, feel free to send me any other topics you'd like to have me write a poem about!