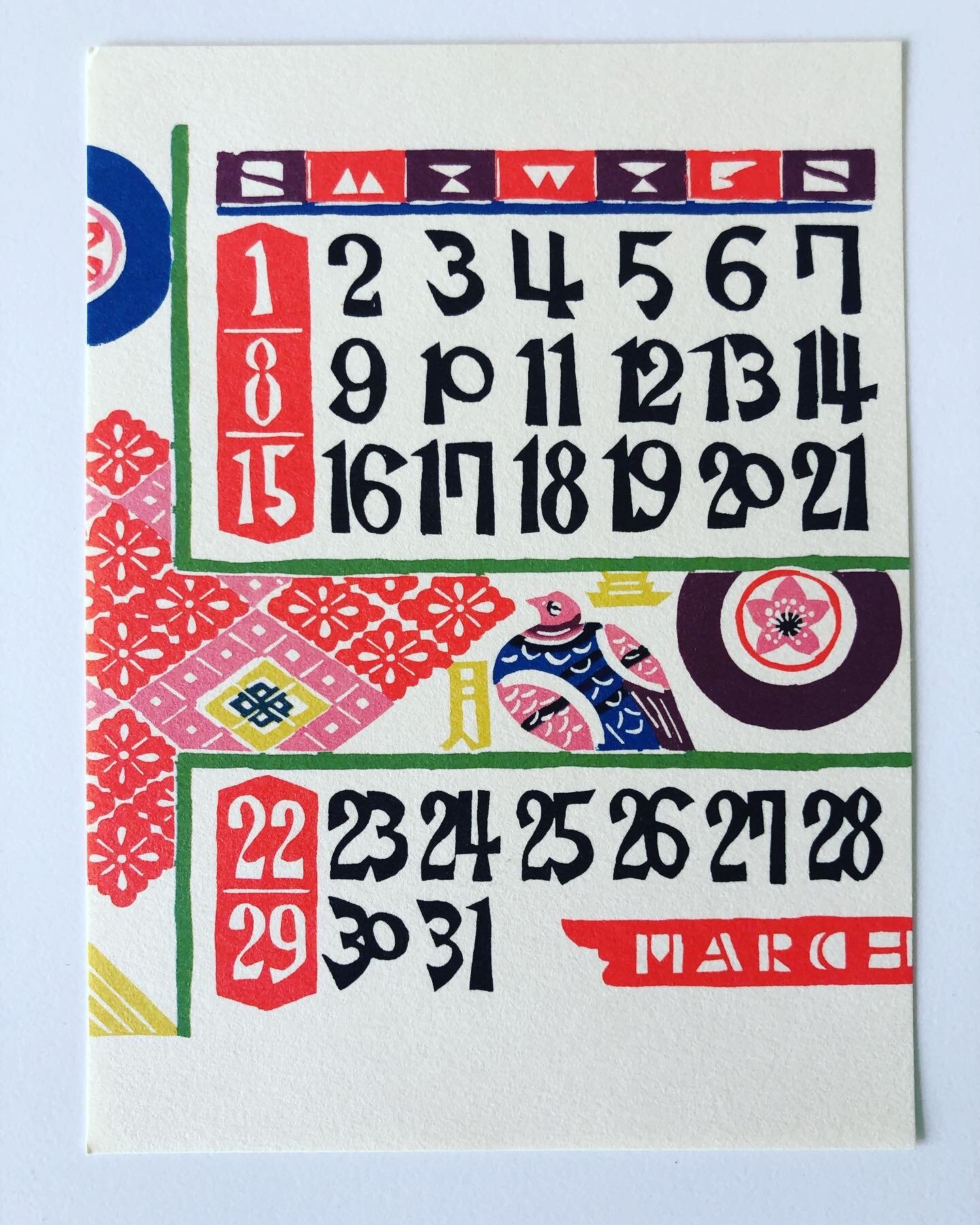

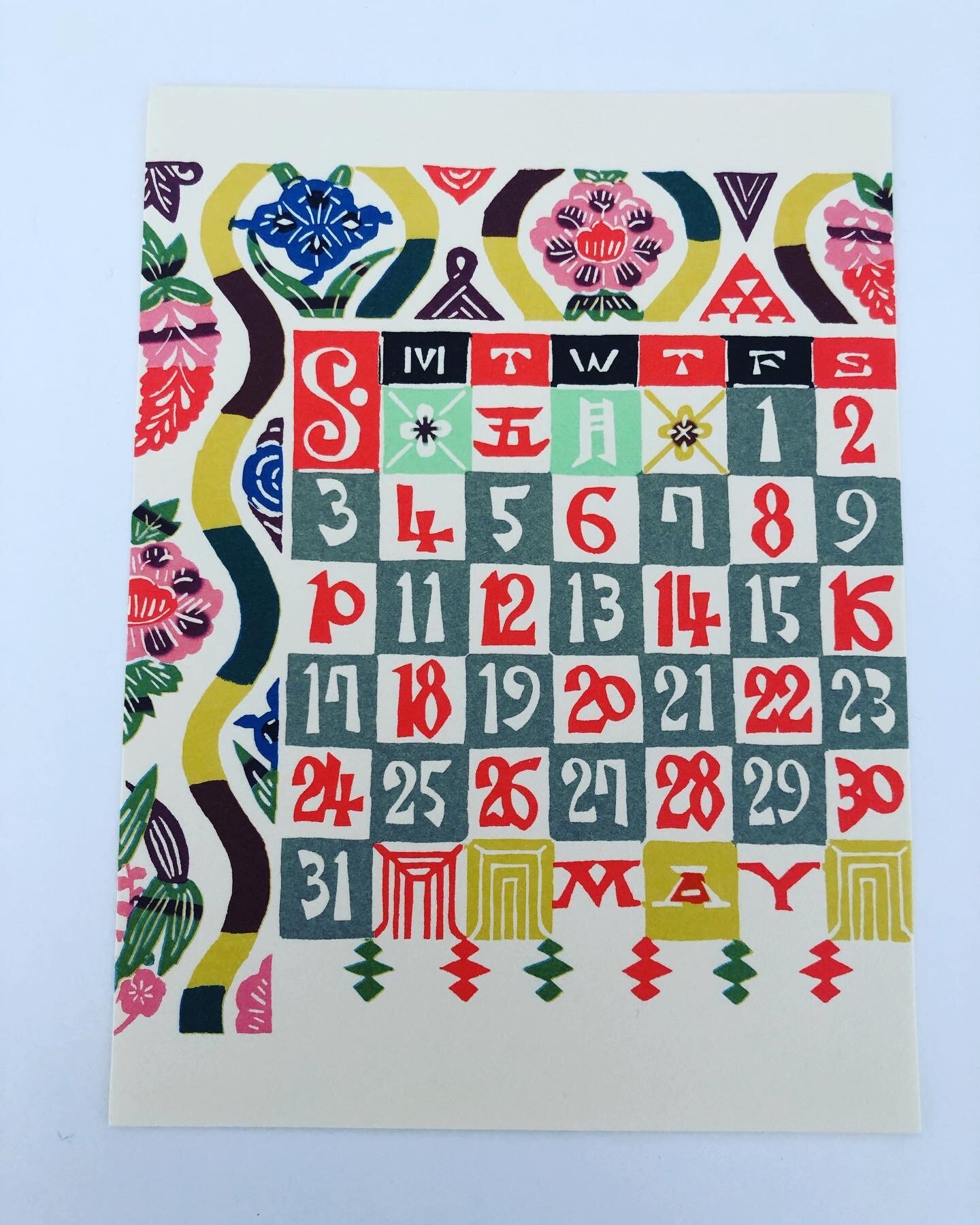

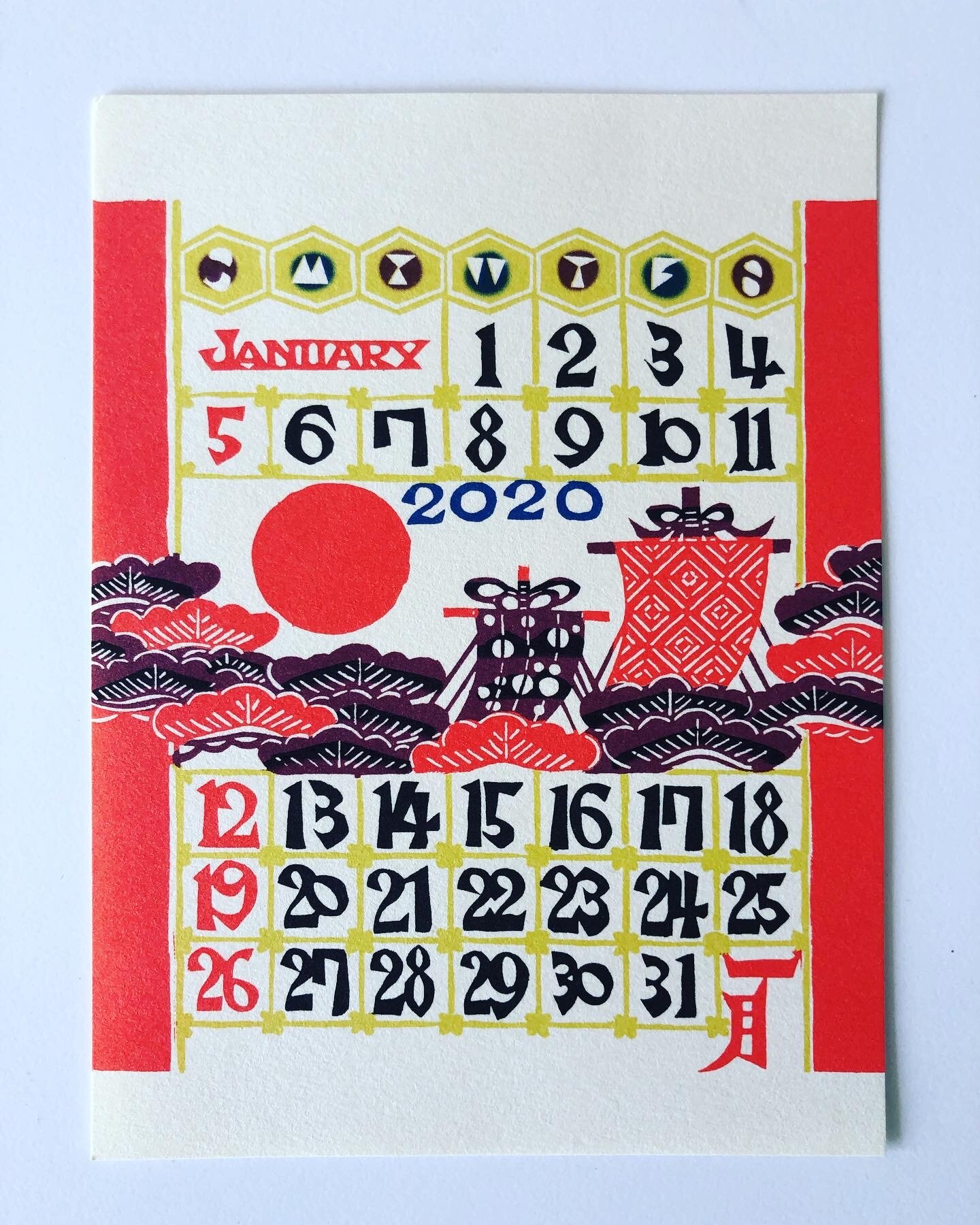

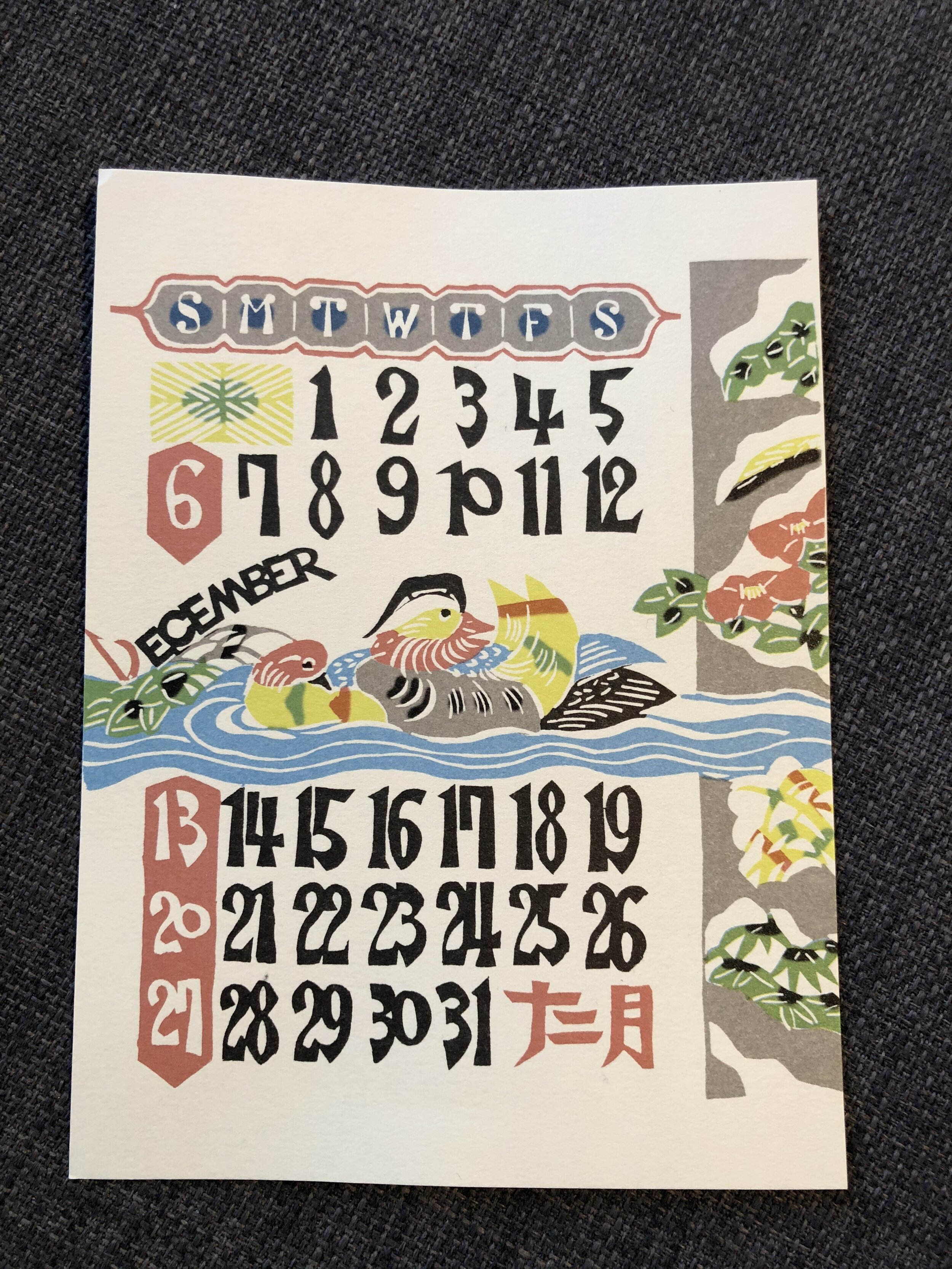

This year, more than any other in my time living in Japan, I was taken by the beauty of woodblock prints. It started with a calendar I had picked up at the end of last year at the Folk Craft Museum with designs by Keisuke Serizawa. His whimsical work follows the Bingata tradition, a hand-dyeing technique that originated in Okinawa. During the lockdown, marking the passage of time by turning to a new page each month was actually something I looked forward to.

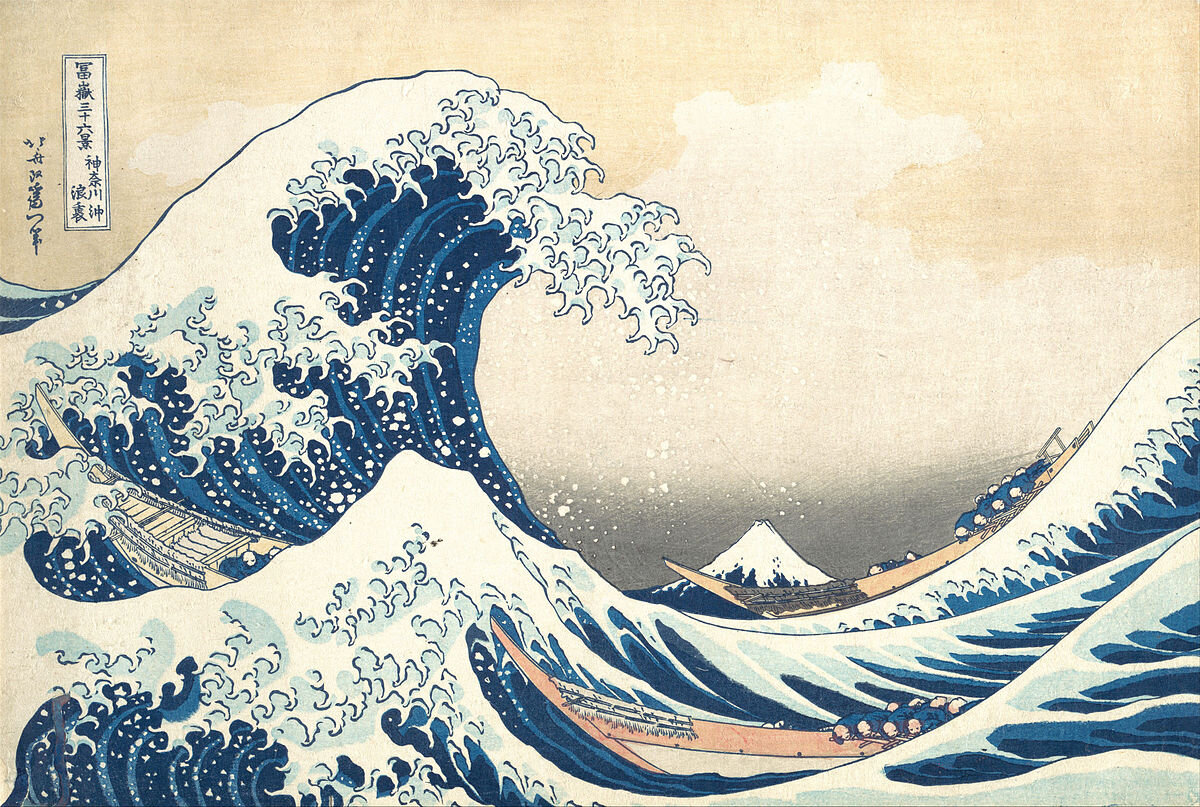

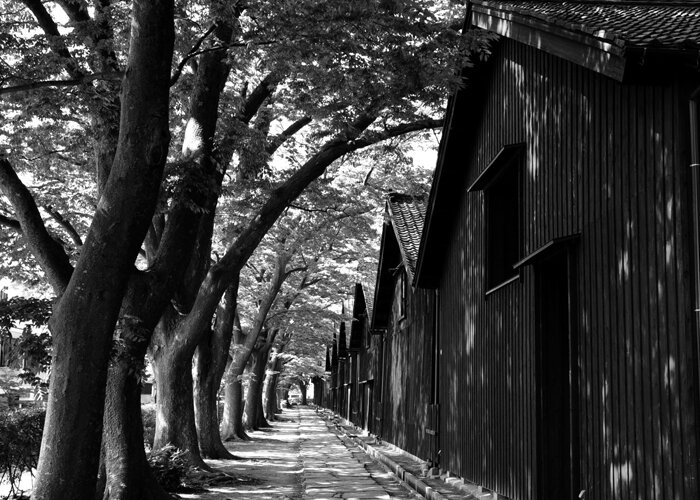

Then in the summer, when the cases were lower, I was able to go to an exhibition of woodblock prints by Shiko Munakata. His works are so dynamic, the high contrast between ink and paper just jumps out at you. Before this exhibition, the only real masters of woodblock print that I had come in contact with were Hokusai and Hiroshige, among others. Their styles were nothing like Munakata’s, who embraced folk art.

The Great Wave by Hokusai

Evening Snow at Kamabara by Hioshige

Running Demon by Munakata

Morning Chrysanthemum by Munakata

My new found love for Munakata’s works reminded me of a quote from Frank Llyod Wright, who himself was a collector of woodblock prints. If you are interested in learning more about Wright’s love of woodblock, I highly recommend, "The Japanese Print: An Interpretation" which has a beautiful collection of essays by Wright about the woodblock prints he collected.

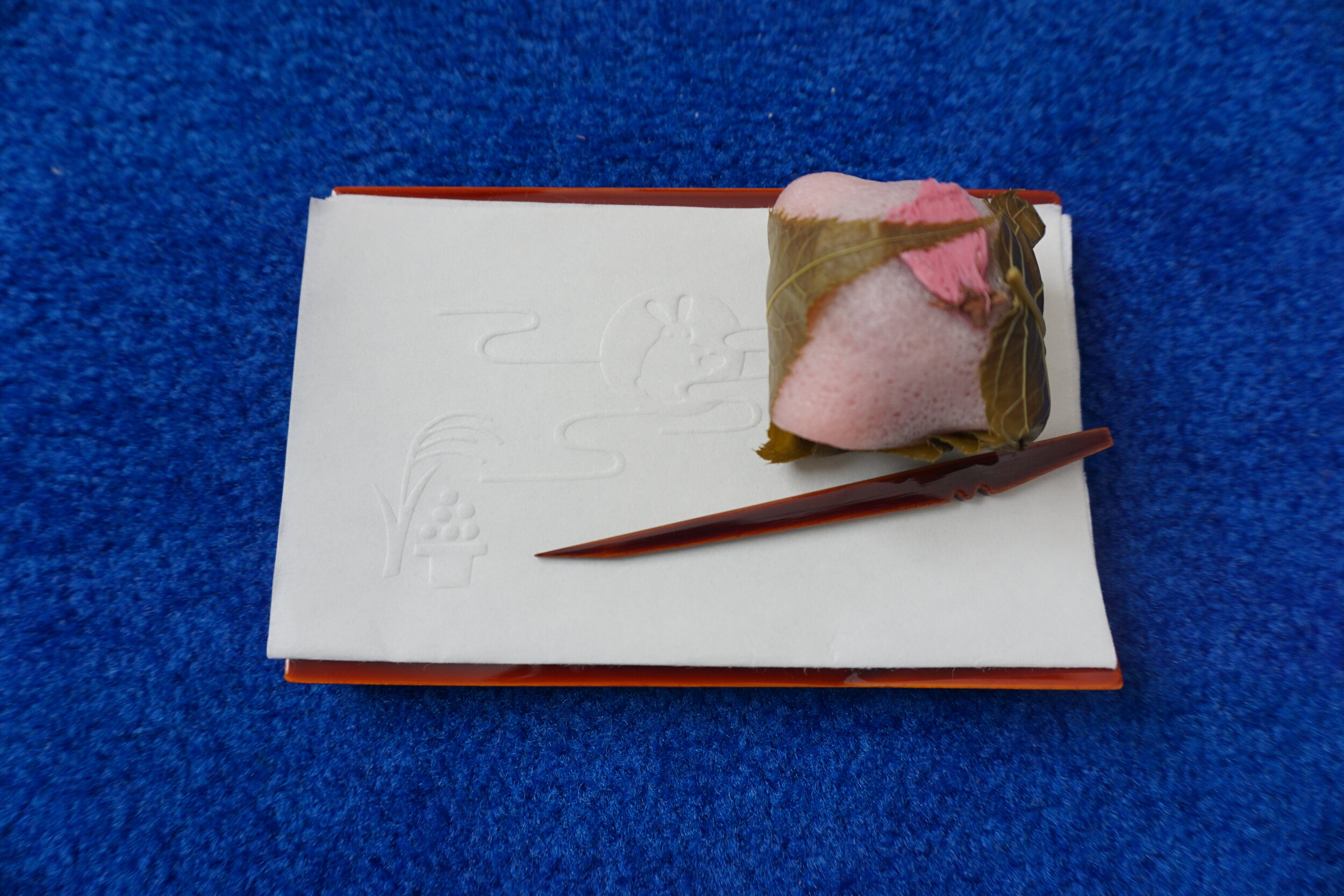

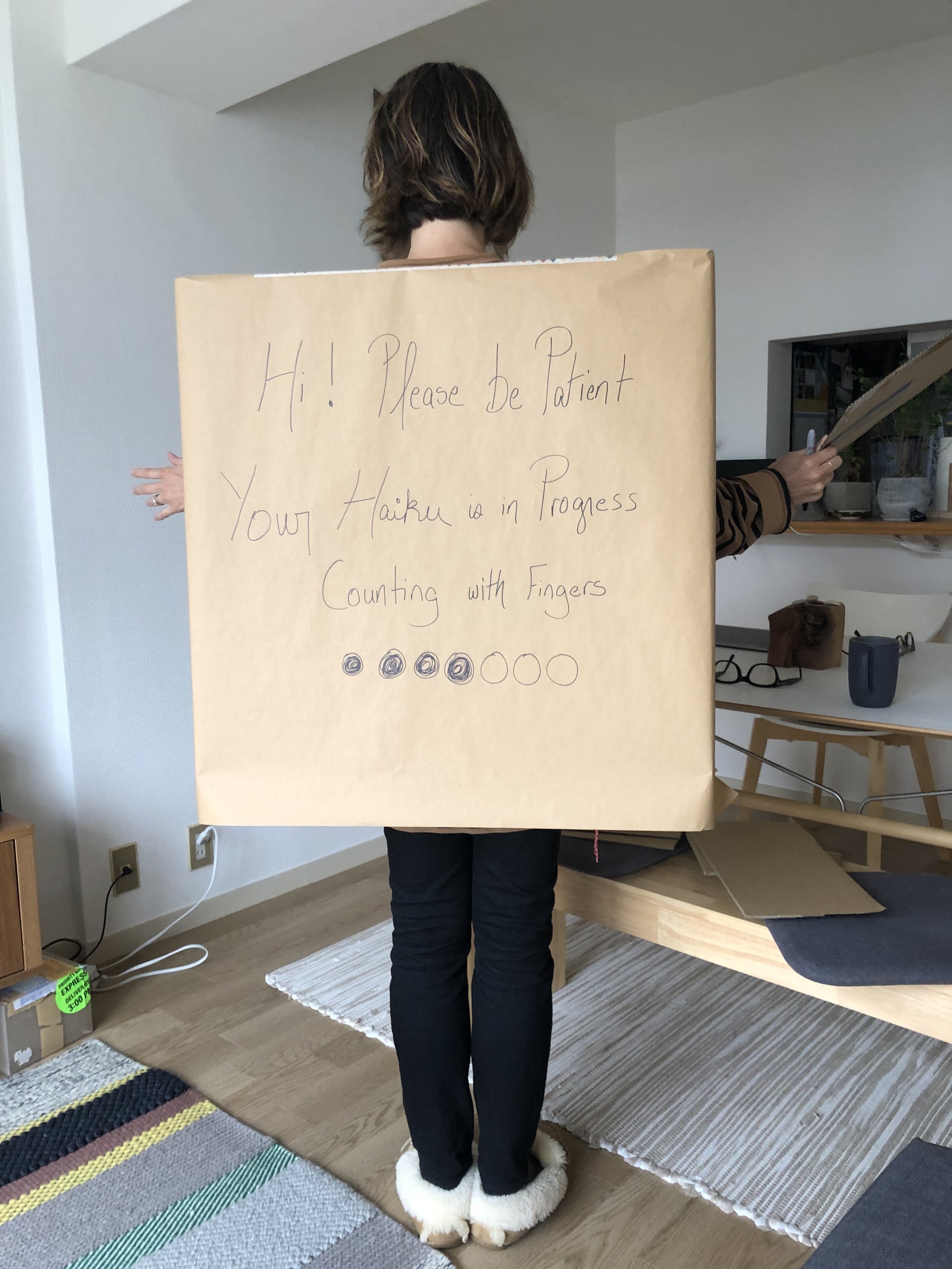

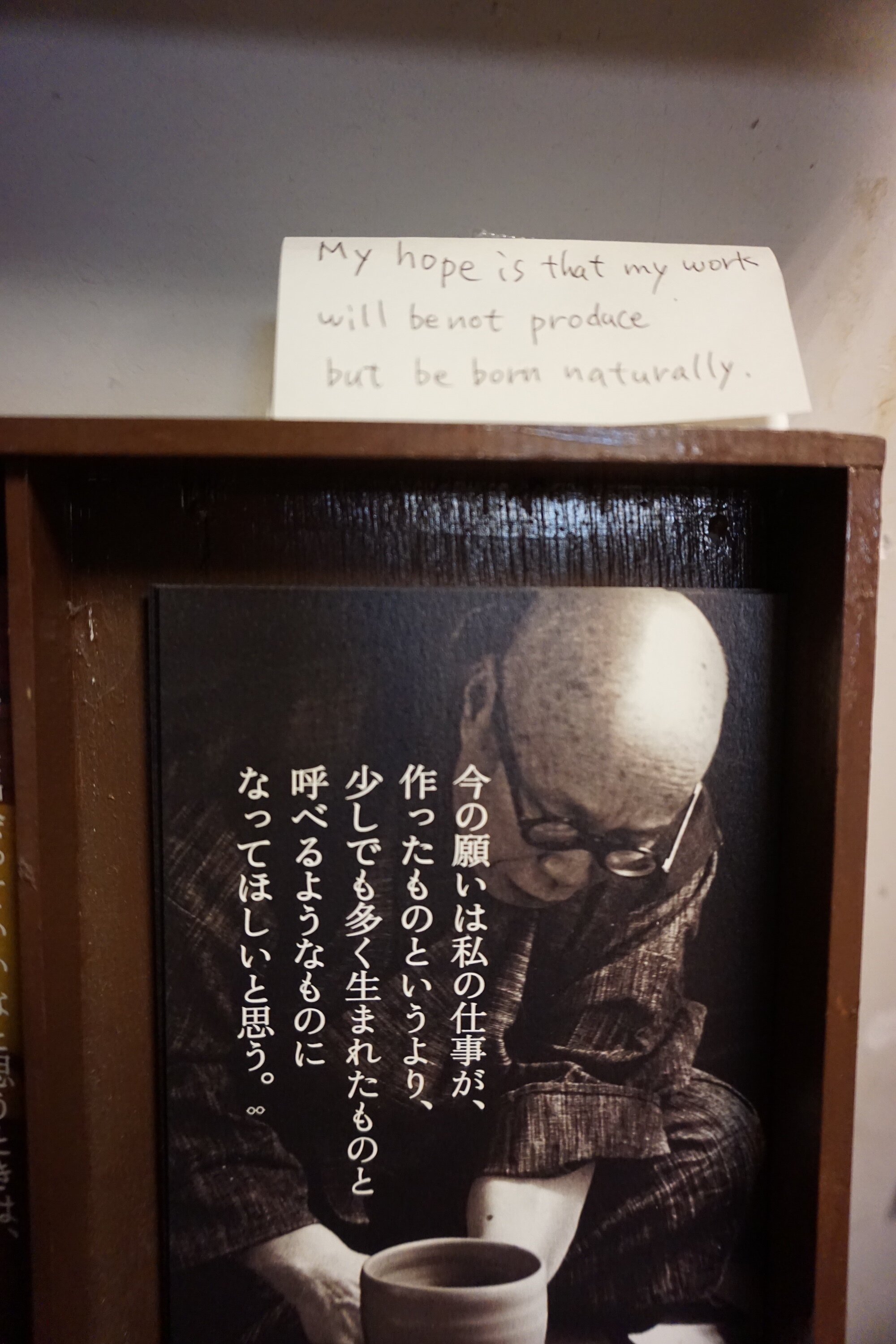

It was with this inspiration and some much-needed encouragement from my friend Shu Kuge, who is a woodblock print artist (amazing WIP carving), that I embarked on making my New Year’s card. The creation of which was not unlike 2020, with its ups and downs. I entered the process with huge expectations and a grand plan, but in the process of sketching, transferring, carving, and printing, was humbled. And the image that resulted ended up only focusing on the most essential elements to get the message across. Is the final product different from my original idea? Yes! But in the end, I like it so much more!

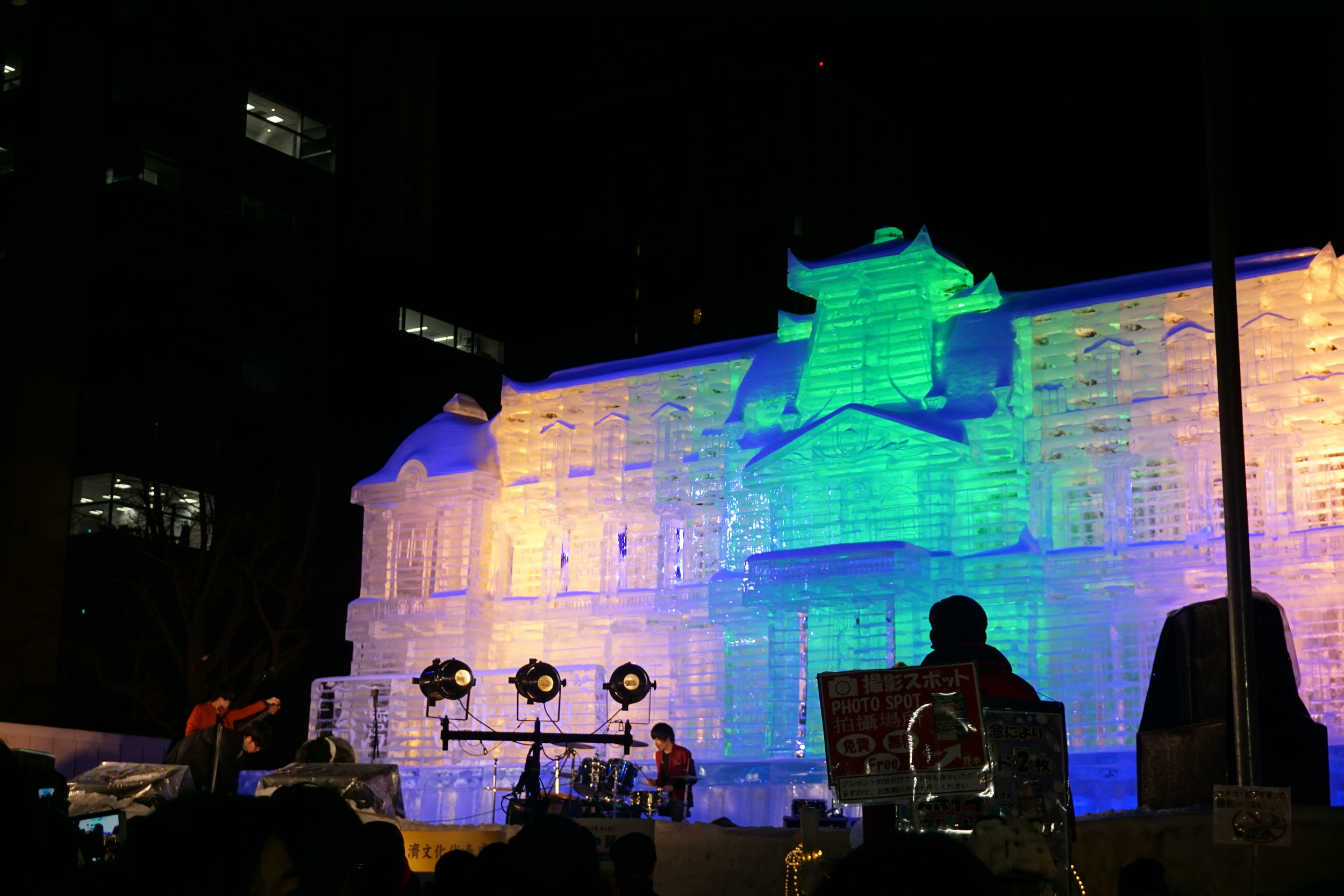

This card is meant to capture the liberation and thrill I felt while learning to ride a scooter earlier this year in Hokkaido. My sincere wish for all of you is that you get to have that same feeling of freedom and fun—when it is safe to do—in 2021.

Happy New Year! Wishing you all the best in the year to come.